MALI VS FRANCE

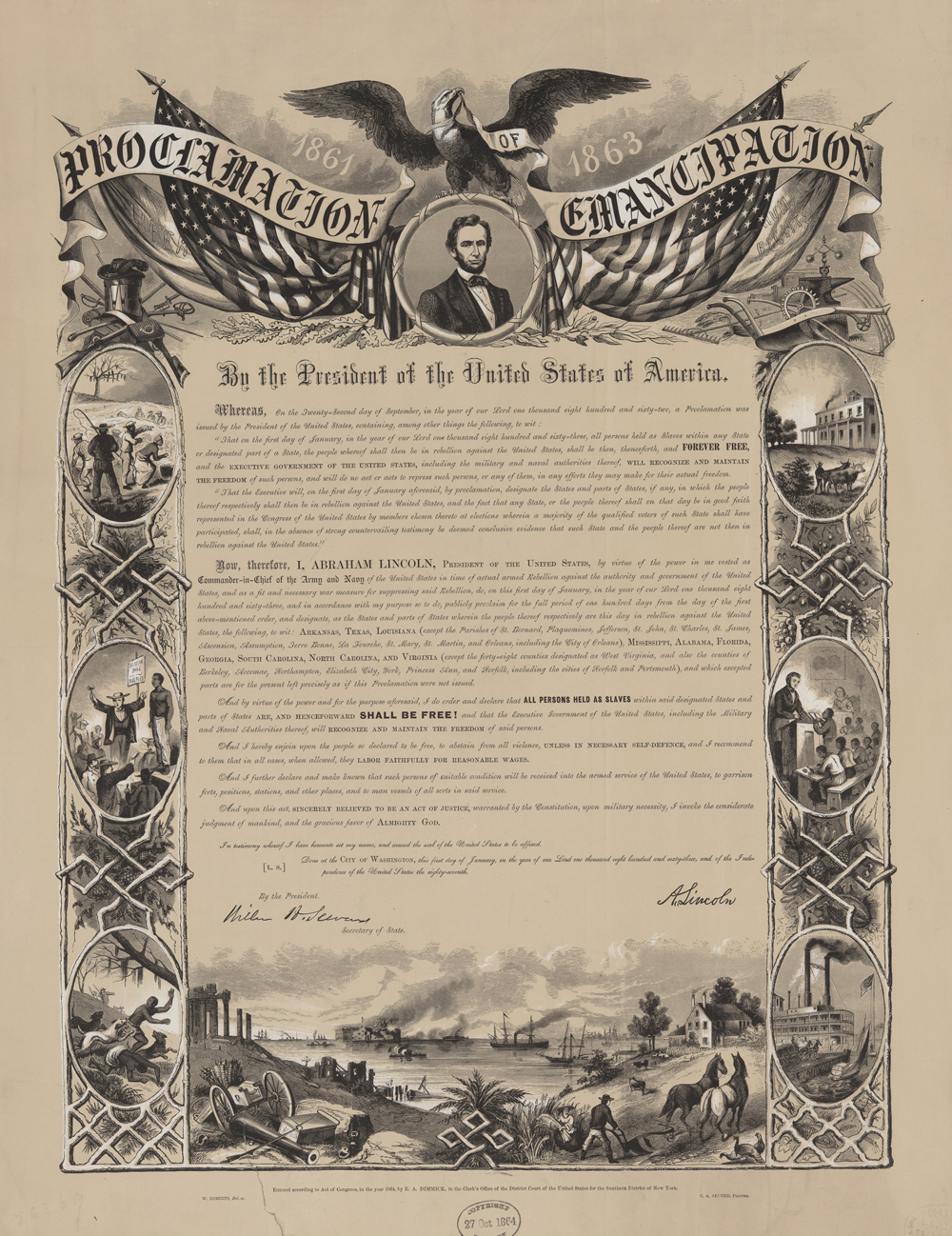

FROM VOULET-CHANOINE’S MASSACRES STARTING IN SEPTEMBER 1898 TO THE “ARMING TERRORISTS” ACCUSATION THAT MALI WANTS THE UN SECURITY COUNCIL TO EXAMINE IN SEPTEMBER 2022.

Dear reader,

Please, take the time to read in this issue of your magazine, the Special Report on “Mali vs France.” We are certain, you will wonder. You will discover surprising facts. To prepare you to put those facts in perspective, which will help to formulate your proper opinion, it is useful a historical background is useful.

The 1960s started with a sudden jump of the number of African countries that became members of the United Nations. 1960 alone saw 15 African countries gaining independence. At the September meeting of that year, the UN General Assembly admitted 17 new States, of which 16 African. Not all of Africa was freed, though.

At the UN, the newly independent African member countries joined forces. In the footstep of panafricanist pioneer Kwame Nkrumah who advocated for the independence of the entire continent, they used the UN as a platform to free the rest of the continent still under the colonialists’ sway. When Ghana became the first independent Sub-Saharan African country on 6 March 1957, Nkrumah warned his compatriots and all the Africans: Ghana’s independence will be meaningless until we liberate the whole of Africa. The liberation battle had to intensify, he advised.

Within the UN, the already freed African countries battled for the independence of the still colonized part of Africa. They became forceful activist states in the UN Special Committee on Decolonization that the UN General Assembly (UNGA) created in 1961, pursuant to the UNGA Resolution 1654(XVI) of 27 November 1961. The UNGA set that special committee to be UNGA’s competent body for decolonization questions. This Special Committee came to be known as the C24 Committee, because of its 24-member states.

Initially, they were 17. Indeed, on 27 November 1961, UNGA Resolution 1654(XVI) created a 17-member special committee in charge of decolonization. They were Australia, Cambodia, Ethiopia, India, Italy, Madagascar, Mali, Poland, Syria, Tanganyika, Tunisia, Soviet Union, United Kingdom, United States of America, Uruguay, Venezuela, and Yugoslavia. At its 1195th plenary meeting on 17 December 1962, that is, 60 years ago, the UNGA added seven other members: Bulgaria, Chile, Denmark, Iran, Iraq, Ivory Coast, and Sierra Leone. The C24 still exists today, with 29 member countries, but it is still known by its original label: C24.

Why recall today, 60 years later, the story of the C24, the UN Special Committee on Decolonization? For one reason: the French government’s and army’s behavior in Mali since 2013. It begs for a new C24 to re-decolonize Africa, at least several African countries, many of which are previous French colonies.

That behavior has been fueling the ongoing crisis between the two states. The crisis culminated on 15 August 2022 with two events: one, the last French soldier left Mali.

Two and unprecedented, through its foreign affairs miniser, the Malian government sent a letter to the President of the UN Security Council, accusing France of very grave misdeeds which include arming and informing the terrorists the French government says it has been fighting in Mali and the Sahel region.

As said earlier, Mali was already at the forefront of the anti-colonialism battle as a C-24-member state in the early 1960s. That battle was President Modibo Keita’s Mali’s hallmark. Like Nkrumah, Keita was a great panafricanist and a member of the famous Casablanca Group that, on 7 January 1961 produced and adopted the “African Charter of Casablanca,” that, as of today, remains the most genuine roadmap for African prosperity and power. The other three leaders of the Casablanca Group were Gamal Abdel Nasser of Egypt, Sékou Touré of Guinea, and King Mohammed V of Morocco.

Since 28 May 2021, Colonel Assimi Goïta is the interim President of Mali. At the head of the National Committee for the Salvation of the People, he led a military coup that overthrew President Ibrahim Boubacar Keita on 18 August 2020. Mr. Bah Ndaw became Malian acting president from 25 September 2020 to 24 May 2021 when Colonel Goïta initiated a second coup against him. On 11 June 2021, the Malian National Transition Council established the transition government that has been leading the country up to today. On 12 August 2021, that council adopted the program of actions the government is charged to implement. The aim is the organization, within 24 months, elections that will bring to power the new civilian and legitimate regime.

Assimi Goïta has significantly changed the pattern of Mali’s internal and external policiy. France hates it.

The confrontation between Paris and Bamako escalated abruptly when the Malian government signed a military agreement with the Russians. When the first Russian soldiers landed in Mali later in 2021, French officials further escalated attacks against Colonel Assimi Goïta and the government of Mali. Since then, the relations between the two countries kept deteriorating. On 14 December 2021, French soldiers left the Malian city of Timbuktu. On 31st January 2022, Mali expelled Joel Meyer, French Ambassador in Mali, giving him 72 hours to leave the country. On 15 August 2022, the last French soldiers left Mali.

That departure did not stop the French officials’ continuous flow of diatribes against the Malian government and the Malian President. Something unprecedented in African geopolitics, perhaps in world affairs, happened that same 15 August 2022: Abdoulaye Diop, Malian Minister of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation wrote a letter to Zhang Jun, the Ambassador of the People’s Republic to the UN, and President of the UN Security Council in New York.

For the first time, an African government challenges in that way a permanent member of the UN Security Council in that very council. What makes the letter exceptional, outstandingly unique, is its object: Mali accuses France of, among other crimes, having violated the Malian space multiple times, conducting acts of “espionage, intimidation or even subversion” against the Malian State. Graver, Minister Diop accuses France of arming terrorists.

Things should have never reached that level of acrimony between the two countries. France should have never behaved as she did in Mali, the genocides France has committed there. One of them crimes is the one Captains Paul Voulet and Julien Chanoine perpetrated in 1898 and 1899. The crime started on Wednesday 21st September 1898 when the so-called “Mission Afrique Centrale” departed on boats on the Niger River in Bamako. The blood of tens of thousands of innocent Africans that mission shed could replace the water of the Niger River.

If history teaches lessons, shouldn’t the first one be the humility that follows repentance? For those who the topic interests, who want to assess the level of gravity of what we’re talking about, reading a book like “A la recherche de Voulet: sur les traces sanglantes de la mission Afrique centrale” (Looking for Voulet: in the bloody footsteps of the Central Africa mission) by Colonel Klobb and Lieutenant Meynier and edited in 2001, will help. On their criminal spree, Voulet and Chanoine terrorized and massacred Africans not only in Mali but in West and parts of Central Africa. Here is an excerpt of the book: “Voulet entered the village, killed a thousand men or women, took the seven hundred best women, and horses and camels, etc.” On the Voulet-Chanoine’s crimes, one can also read Bertrand Taithe’s book, “The killer trail: A colonial scandal in the heart of Africa,” that Oxford University Press published in 2009.

One month and six days before the 124th anniversary of the start of the massacres Voulet and Chanoine committed against Mali, then called “French Sudan,” the government of Mali takes France to the world court that the United Nations Organization is. If France is found guilty, would she escape punishment like she has been doing for the past 124 years of the Voulet-Chanoine’s massacres? Is the United Nations Organization a fair court? The 77th UN General Assemby starts on 13 September 2022, 8 days before the 124th anniversary. Will the UN accept to hear and examine Mali’s accusations? Can Africans rely on the UN as a fair institution?

FROM VOULET-CHANOINE’S MASSACRES STARTING IN SEPTEMBER 1898 TO THE “ARMING TERRORISTS” ACCUSATION THAT MALI WANTS THE UN SECURITY COUNCIL TO EXAMINE IN SEPTEMBER 2022.

D

ear reader,

Please, take the time to read in this issue of your magazine, the Special Report on “Mali vs France.” We are certain, you will wonder. You will discover surprising facts. To prepare you to put those facts in perspective, which will help to formulate your proper opinion, it is useful a historical background is useful.

The 1960s started with a sudden jump of the number of African countries that became members of the United Nations. 1960 alone saw 15 African countries gaining independence. At the September meeting of that year, the UN General Assembly admitted 17 new States, of which 16 African. Not all of Africa was freed, though.

At the UN, the newly independent African member countries joined forces. In the footstep of panafricanist pioneer Kwame Nkrumah who advocated for the independence of the entire continent, they used the UN as a platform to free the rest of the continent still under the colonialists’ sway. When Ghana became the first independent Sub-Saharan African country on 6 March 1957, Nkrumah warned his compatriots and all the Africans: Ghana’s independence will be meaningless until we liberate the whole of Africa. The liberation battle had to intensify, he advised.

Within the UN, the already freed African countries battled for the independence of the still colonized part of Africa. They became forceful activist states in the UN Special Committee on Decolonization that the UN General Assembly (UNGA) created in 1961, pursuant to the UNGA Resolution 1654(XVI) of 27 November 1961. The UNGA set that special committee to be UNGA’s competent body for decolonization questions. This Special Committee came to be known as the C24 Committee, because of its 24-member states.

Initially, they were 17. Indeed, on 27 November 1961, UNGA Resolution 1654(XVI) created a 17-member special committee in charge of decolonization. They were Australia, Cambodia, Ethiopia, India, Italy, Madagascar, Mali, Poland, Syria, Tanganyika, Tunisia, Soviet Union, United Kingdom, United States of America, Uruguay, Venezuela, and Yugoslavia. At its 1195th plenary meeting on 17 December 1962, that is, 60 years ago, the UNGA added seven other members: Bulgaria, Chile, Denmark, Iran, Iraq, Ivory Coast, and Sierra Leone. The C24 still exists today, with 29 member countries, but it is still known by its original label: C24.

Why recall today, 60 years later, the story of the C24, the UN Special Committee on Decolonization? For one reason: the French government’s and army’s behavior in Mali since 2013. It begs for a new C24 to re-decolonize Africa, at least several African countries, many of which are previous French colonies.

That behavior has been fueling the ongoing crisis between the two states. The crisis culminated on 15 August 2022 with two events: one, the last French soldier left Mali.

Two and unprecedented, through its foreign affairs miniser, the Malian government sent a letter to the President of the UN Security Council, accusing France of very grave misdeeds which include arming and informing the terrorists the French government says it has been fighting in Mali and the Sahel region.

As said earlier, Mali was already at the forefront of the anti-colonialism battle as a C-24-member state in the early 1960s. That battle was President Modibo Keita’s Mali’s hallmark. Like Nkrumah, Keita was a great panafricanist and a member of the famous Casablanca Group that, on 7 January 1961 produced and adopted the “African Charter of Casablanca,” that, as of today, remains the most genuine roadmap for African prosperity and power. The other three leaders of the Casablanca Group were Gamal Abdel Nasser of Egypt, Sékou Touré of Guinea, and King Mohammed V of Morocco.

Since 28 May 2021, Colonel Assimi Goïta is the interim President of Mali. At the head of the National Committee for the Salvation of the People, he led a military coup that overthrew President Ibrahim Boubacar Keita on 18 August 2020. Mr. Bah Ndaw became Malian acting president from 25 September 2020 to 24 May 2021 when Colonel Goïta initiated a second coup against him. On 11 June 2021, the Malian National Transition Council established the transition government that has been leading the country up to today. On 12 August 2021, that council adopted the program of actions the government is charged to implement. The aim is the organization, within 24 months, elections that will bring to power the new civilian and legitimate regime.

Assimi Goïta has significantly changed the pattern of Mali’s internal and external policiy. France hates it.

The confrontation between Paris and Bamako escalated abruptly when the Malian government signed a military agreement with the Russians. When the first Russian soldiers landed in Mali later in 2021, French officials further escalated attacks against Colonel Assimi Goïta and the government of Mali. Since then, the relations between the two countries kept deteriorating. On 14 December 2021, French soldiers left the Malian city of Timbuktu. On 31st January 2022, Mali expelled Joel Meyer, French Ambassador in Mali, giving him 72 hours to leave the country. On 15 August 2022, the last French soldiers left Mali.

That departure did not stop the French officials’ continuous flow of diatribes against the Malian government and the Malian President. Something unprecedented in African geopolitics, perhaps in world affairs, happened that same 15 August 2022: Abdoulaye Diop, Malian Minister of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation wrote a letter to Zhang Jun, the Ambassador of the People’s Republic to the UN, and President of the UN Security Council in New York.

For the first time, an African government challenges in that way a permanent member of the UN Security Council in that very council. What makes the letter exceptional, outstandingly unique, is its object: Mali accuses France of, among other crimes, having violated the Malian space multiple times, conducting acts of “espionage, intimidation or even subversion” against the Malian State. Graver, Minister Diop accuses France of arming terrorists.

Things should have never reached that level of acrimony between the two countries. France should have never behaved as she did in Mali, the genocides France has committed there. One of them crimes is the one Captains Paul Voulet and Julien Chanoine perpetrated in 1898 and 1899. The crime started on Wednesday 21st September 1898 when the so-called “Mission Afrique Centrale” departed on boats on the Niger River in Bamako. The blood of tens of thousands of innocent Africans that mission shed could replace the water of the Niger River.

If history teaches lessons, shouldn’t the first one be the humility that follows repentance? For those who the topic interests, who want to assess the level of gravity of what we’re talking about, reading a book like “A la recherche de Voulet: sur les traces sanglantes de la mission Afrique centrale” (Looking for Voulet: in the bloody footsteps of the Central Africa mission) by Colonel Klobb and Lieutenant Meynier and edited in 2001, will help. On their criminal spree, Voulet and Chanoine terrorized and massacred Africans not only in Mali but in West and parts of Central Africa. Here is an excerpt of the book: “Voulet entered the village, killed a thousand men or women, took the seven hundred best women, and horses and camels, etc.” On the Voulet-Chanoine’s crimes, one can also read Bertrand Taithe’s book, “The killer trail: A colonial scandal in the heart of Africa,” that Oxford University Press published in 2009.

One month and six days before the 124th anniversary of the start of the massacres Voulet and Chanoine committed against Mali, then called “French Sudan,” the government of Mali takes France to the world court that the United Nations Organization is. If France is found guilty, would she escape punishment like she has been doing for the past 124 years of the Voulet-Chanoine’s massacres? Is the United Nations Organization a fair court? The 77th UN General Assemby starts on 13 September 2022, 8 days before the 124th anniversary. Will the UN accept to hear and examine Mali’s accusations? Can Africans rely on the UN as a fair institution?